Psychedelic Lichen

A newly discovered species of lichen from the rain forests of Ecuador proves that you don’t have to be a magic mushroom to contain psilocybin. It is the first and only lichen known to incorporate these substances.

Ask any biologist and he’ll tell you lichens are an intriguing bunch. They exist only because of a symbiotic relationship between algae (or cyanobacteria) and fungi. The fungus creates a network that sustains, hydrates and protects the alga, which in turn provides sugars through photosynthesis. So, while they exhibit plant-like characteristics, they are not plants. They are composite organisms. This makes the case of the psychedelic lichen even more interesting.

According to a scientific paper published in The Bryologist, the recently classified lichen exhibitspresumed hallucinogenic properties. The scientific method requires that researchers be thorough and only state things that were rigorously tested. That is why they included the word presumed. The elusive lichen is decidedly psychedelic, as evidenced by reports from the tribe who knew about its existence, but since researchers weren’t permitted to use pure reference compounds, they were unable to positively determine the presence of hallucinogenic substances.

The story behind the discovery of this trippy organism is about as compelling as they get. In 1981, ethnobotanists Jim Yost and Wade Davis were out doing field work in the dense Ecuadorian rainforests when a tribe called the Waorani pointed them in the right direction. Yost had heard of the existence of a hallucinogenic lichen but it was so rare he had never had a chance to encounter one, despite having searched for it for seven years. In a 1983 paper that detailed their discovery, the ethnobotanists wrote:

“In the spring of 1981, whilst we were engaged in ethnobotanical studies in eastern Ecuador, our attention was drawn to a most peculiar use of hallucinogens by the Waorani, a small isolated group of some 600 Indians. … Amongst most Amazonian tribes, hallucinogenic intoxication is considered to be a collective journey into the subconscious and, as such, is a quintessentially social event.

The Waorani, however, consider the use of hallucinogens to be an aggressive anti-social act; so the shaman, or ido, who desires to project a curse takes the drug alone or accompanied only by his wife at night in the secrecy of the forest or in an isolated house. …”

The lichen was so rare that not even the Waorani people had any. And if the small tribe that maintains a strong connection with the surrounding environment isn’t holding, you know the thing is rare. In fact, it doesn’t get any rarer than that. The Waorani called it nɇnɇndapɇ and told the botanists their shamans once used it, but the last time that happened was “some four generations ago — approximately eighty years — when ‘bad shaman ate it to send a curse to cause other Waorani to die.’”

Waorani hunters

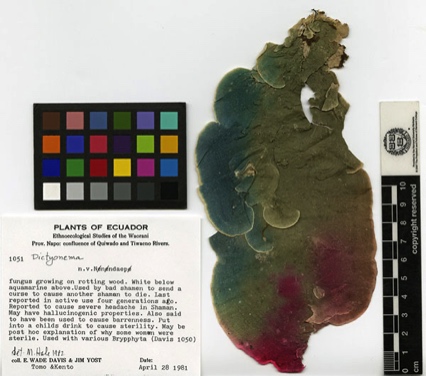

Spurred on by the lichen’s scarcity, the duo intensified their efforts and soon got their payoff. As if guided by an invisible hand, Yost and Davis became the first westerners to lay their eyes on the nigh intangible nɇnɇndapɇ. Being responsible investigators, they preserved the unique specimen for future analysis.

It would be another three decades before the lichen’s DNA was analyzed, showing that it was indeed a new species. In 2014, a team of researchers led by Michaela Schmull christened the lichen Dictyonema huaorani and used a technique called liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to determine the chemical compounds existent in its tissue. Tests showed the presence of psilocybin, tryptamine, 5-MeO-DMT, 5-MeOT (5-methoxytryptamine), 5-MeO-NMT and 5-MT.

This composition makes D. huaorani a very interesting specimen, in the sense that this specific cocktail of substances has never been found before in any plant, fungus or animal. However, the researchers concluded that:

“Due to our inability to use pure reference compounds and scarce amount of sample for compound identification, however, our analyses were not able to determine conclusively the presence of hallucinogenic substances.”

So it seems further research into potentially beneficial species is once again halted by willfully misguided legislation. This trend has been going on for far too long but voices are starting to get louder and louder.